Final Draft of Egg Fairness Regulations Reviewed

Published on : 11 Feb 2026

The proposals were presented to the BFREPA board on February 10th at the Ramada Hotel in Telford...

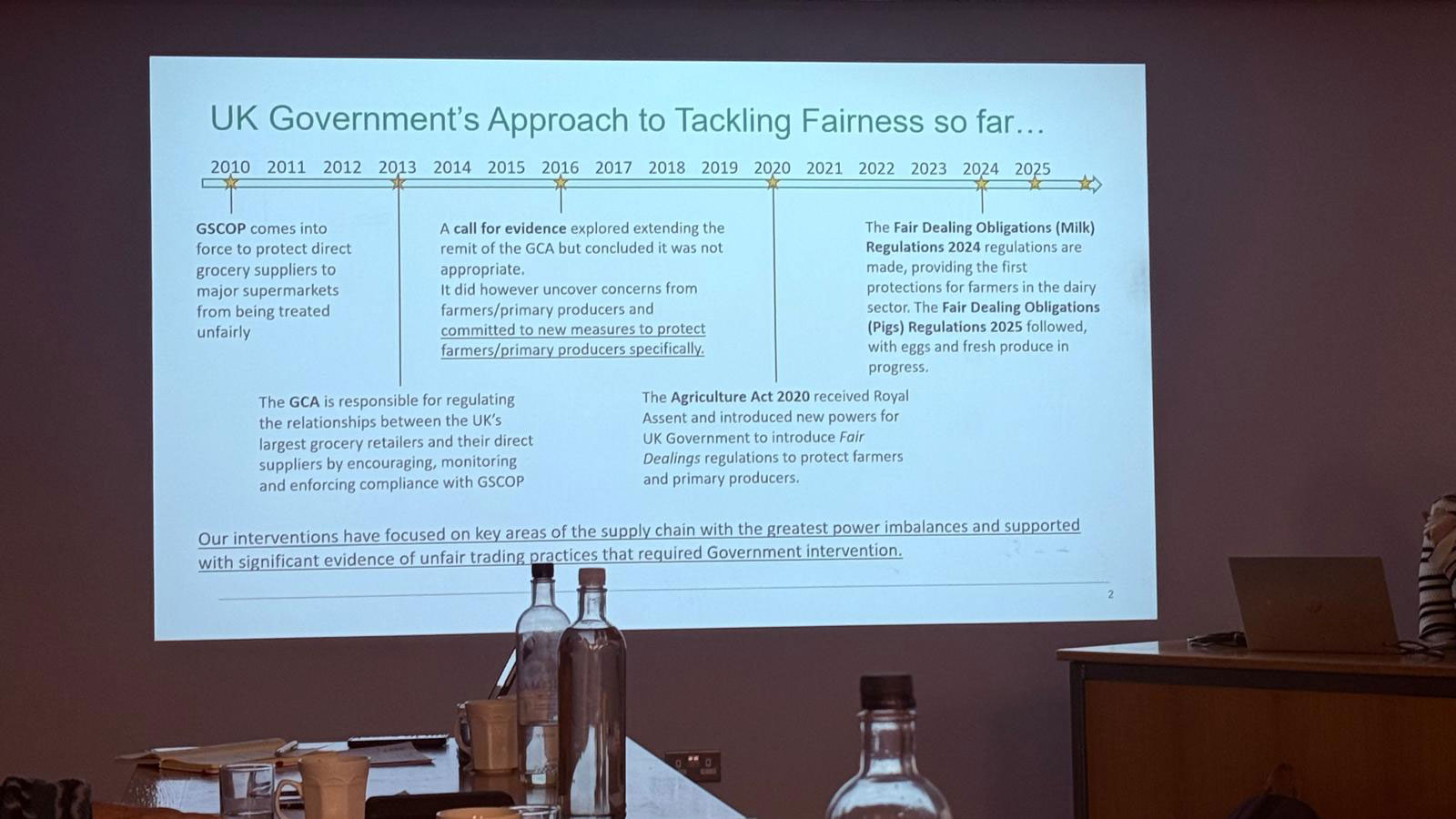

The latest version of the Fairness in the Supply Chain proposals for eggs was presented to the BFREPA board at its recent meeting at the Ramada Hotel in Telford, marking what Defra expects to be the final stage of policy development before the regulations move into legal drafting. Two Defra officials attended the meeting to provide a detailed update on progress, explain the thinking behind version three, and answer questions from board members on the remaining areas of concern.The session formed part of Defra’s ongoing engagement with industry as it works towards finalising regulations intended to improve contractual fairness for egg producers. While the overall framework is now well advanced, the discussion focused on getting support from BFREPA and the rest of the sector to ensure all final issues are resolved for the regulations to work effectively in practice. Among these were the treatment of producers who are also registered packing centres, termination clauses, special incentives, and the handling of short term or spot sales.Defra began by setting the proposals within the wider context of Government policy on agricultural supply chains. The Groceries Supply Code of Practice, introduced in 2010, provides protections for direct suppliers to major retailers but does not extend to farmers and primary producers operating further upstream. Evidence gathered through subsequent calls for evidence highlighted power imbalances and unfair trading practices affecting producers, leading to new powers under the Agriculture Act 2020. These powers allow Government to introduce sector specific Fair Dealings regulations where there is clear evidence of imbalance.The dairy sector was the first to see those powers used, with the Fair Dealing Obligations Milk Regulations coming into force in 2024. Similar regulations followed in pigs, and eggs are now progressing through the same framework. Throughout, Defra’s stated intention has been to focus protections on primary producers at the earliest stage of the supply chain, where bargaining power is weakest.Consultation on the egg sector ran from December 2023 to February 2024, with a summary of responses published in May 2024. That document highlighted evidence of unfair practices and a clear case for intervention. The first draft of the egg Fair Dealings proposals was published in March 2025, followed by a second version in summer 2025 after extensive stakeholder engagement. Feedback on that version closed in September, and further refinement led to version three being circulated in January 2026, with a deadline of 20 February for final comments. Defra indicated that this version is expected to form the basis of the final policy position before drafting begins.

The underlying aim of the Fair Dealings framework is to protect primary producers rather than regulate the entire downstream chain...

One of the most significant areas of discussion at the Telford meeting was the scope of the regulations and, in particular, how they define which producers are protected. Ministers have decided to maintain the scope so that protections apply to egg producers only, with packers and processors excluded on the basis that many are already covered by the Groceries Supply Code of Practice in their retail dealings. Defra explained that this approach is consistent with the underlying aim of the Fair Dealings framework, which is to protect primary producers rather than regulate the entire downstream chain.However, defining who qualifies as a protected producer has proven to be one of the most complex aspects of the policy. Under the current draft, scope is defined as applying to a primary producer that is not also a registered egg packing centre with APHA. Defra acknowledged that this wording has raised serious concerns across the sector, but wanted to provide assurances that the policy has not changed – producers are intended to be protected – and are looking for support to ensure final language reflects this.Defra data shows that there are 585 producers registered with Defra who also pack, demonstrating that this is not a marginal issue affecting a small number of businesses. Board members stressed that without careful drafting, a significant number of genuine egg producers could be unintentionally excluded from the protections the regulations are intended to deliver.Many producers register as packing centres for practical reasons, such as selling small volumes of eggs at the farm gate, rather than because their primary business is packing or supplying retailers. In these cases, the producer remains firmly within a traditional producer packer relationship for the majority of their output. Using registration status alone as a determining factor risks failing to reflect commercial reality and could undermine the core objective of fairness.Further discussion highlighted the operational grey area between farm gate sales, vending machines, small scale local supply and fully commercial packing operations. Being registered as a packing centre allows eggs to be graded and marketed as Class A, and some producer packers also buy in eggs from other producers at certain times of year. This creates a spectrum of business models rather than a simple producer versus packer divide. Board members emphasised that the legal definition must capture intent and commercial function, not simply registration status, otherwise a wide range of mixed businesses could be misclassified.Defra acknowledged the scale and importance of the issue and confirmed that work is ongoing to refine the wording so that producers are not inadvertently excluded, and welcomed input on this. Board members made clear that this point is fundamental to the success of the regulations and must be resolved before the policy moves into law, and offered to share a proposal to do so.Related concerns were also raised around producers who sell eggs through agents or intermediaries rather than contracting directly with a packing company. The board sought reassurance that protections would follow the producer through the contractual chain and that alternative commercial structures would not create loopholes or leave producers exposed.The concept of a written notice to disapply, effectively allowing certain short term sales to sit outside the full regulatory framework, was another area examined. Earlier drafts included a £1000 threshold, but feedback suggested this was too restrictive and risked unintended consequences. Defra confirmed that the threshold has now been removed in version three.The notice to disapply will require a clear written trail, with the producer giving written notice prior to the agreement being made. Officials stressed that this mechanism is designed to support legitimate short term or spot sales outside long term agreements and is not intended to override or undermine existing contractual commitments. Where a producer has committed a defined percentage of production under a long term agreement, those commitments remain binding. The notice to disapply cannot be used to legitimise breaches of contract and does not create a route for informal or off book trading.The intention is to allow flexibility where genuine short term transactions occur, without imposing disproportionate administrative burdens. Board members emphasised that any such flexibility must not weaken core contractual protections or undermine confidence in longer term agreements.In addition to these structural issues, the board examined the role of special incentives within supply agreements and how these interact with contract termination. While incentives such as bonuses, loyalty payments or additional premiums can form a legitimate part of commercial arrangements, they must not be structured or deployed in a way that effectively prevents a producer from terminating a contract.The principle discussed was clear: special incentives must not be used as an instrument to restrict a producer’s right to give notice in accordance with the contract. If a producer chooses to terminate within agreed terms, incentives should not be withdrawn purely as a consequence of exercising that right. To do so would risk undermining the fairness the regulations are intended to establish.Board members stressed that fairness cannot operate in practice if financial mechanisms create indirect barriers to exit. Incentives should reward performance or agreed commitments, but they must not function as a penalty for lawful termination. Transparency, proportionality and clarity in how incentives are structured and applied will therefore be critical in the final drafting of the regulations.At the same time, there was clear debate around commercial freedom and contractual transparency. Some board members argued that where a loyalty bonus or premium is clearly set out in a transparent contract, agreed by both parties at the outset, and forms part of the negotiated price structure, it represents commercial choice rather than unfairness. Questions were raised about whether prohibiting certain incentive structures could inadvertently remove value from producer contracts or limit flexibility in negotiations.Defra responded that evidence gathered during consultation suggested some producers felt unable to exit agreements due to financial mechanisms operating during lengthy notice periods. The department maintained that the objective is not to eliminate commercial incentives, but to prevent them from functioning as structural barriers to termination.Termination clauses more broadly were also examined. Producers require adequate notice periods and protection against unilateral termination in order to plan investments and manage risk. Stability and certainty are essential for long term farm businesses, and clear, enforceable termination provisions sit at the heart of meaningful fairness.Defra clarified that variable pricing mechanisms remain permissible under the proposals and may reflect market conditions as well as cost movements, provided they are transparent and clearly defined within the contract. The intention is not to eliminate commercial pricing flexibility, but to ensure that contractual terms governing changes and termination are clear, fair and enforceable.Board members also sought clarity on the transition from policy to formal regulation and subsequent guidance. Defra confirmed that once translated into legal text, the regulations will be accompanied by guidance intended to explain and interpret the legislation rather than redesign it. Officials emphasised that the current stage represents the final opportunity to influence substantive policy, as future engagement will focus on interpretation and implementation.Defra concluded by outlining the next steps. Version three is expected to be the final policy iteration, and Defra is seeking any remaining written feedback before the drafting stage begins. Following this, the department’s legal team will prepare the regulations, which will then be shared for review to ensure the legal text accurately reflects the agreed policy intent before progressing through Parliamentary procedures.The meeting at the Ramada Hotel provided the BFREPA board with a timely opportunity to scrutinise the latest proposals and ensure members’ concerns are clearly articulated at this crucial stage. It also demonstrated the growing role and influence of BFREPA in representing producers’ interests at national level. The association’s ability to command an audience with Defra and to present detailed, evidence based concerns on behalf of members reflects how far BFREPA has come. As the Fairness in the Supply Chain framework approaches its final form, the precision of the wording will determine whether it delivers genuine, workable protection for egg producers. BFREPA will continue to engage constructively with Defra to ensure the final regulations are proportionate, practical and firmly aligned with the realities of the sector.